Smart Spaces for Making: Networked Physical Tools to Support Process Documentation and Learning

by Marti Louw and Daragh Byrne

Key Ideas

The partnership led to a new vision of ‘documentation’ tools that support students as they engage in self-directed learning activities. Transformation is enabled by a strong focus in the participatory design process on hearing from partners, designing with partners, and creating appropriate ways to rapidly prototype designs with partners that enhance existing valued practices rather than introducing new ones. Successful collaborations require that partners create timelines that account for the resources, time, and effort needed to undertake the complex work that benefits everyone.

Background

Smart Spaces for Making (NSF grant IIS 1736189) began as an exploratory design-based research project to examine how emerging technologies can be used to address the challenge of helping students easily and consistently document their work process in creative educational environments such as project-based, maker, and self-directed learning experiences.

To explore documentation both for assessment and as a creative practice, the Pittsburgh-based project brought together a multidisciplinary group of researchers from Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) and the University of Pittsburgh with practice partners in an extended learning design inquiry process. The research team included expertise in design and design research, learning sciences, human-computer interaction, interactive computing, and the internet of things. Building on existing relationships and past projects, we developed close collaborative relationships with three sites, whose instructional leads and programs deeply valued hands-on creative inquiry and were curious about how to better integrate documentation into creative learning experiences (Stol et al., 2023).

Specifically, our partners are pictured in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. The three partner sites and their creative, collaborative learning workspaces that we grounded our work on. Bottom Left: The library which houses a makerspace and careers education at Quaker Valley High School. Bottom Middle: The Physical Computing Lab is used for in-class and out-of-class experimentation with creative electronics and interactive hardware devices at Carnegie Mellon University. Bottom Right: AlphaLabGear’s makerspace is used to support innovation and entrepreneurship summer programming for urban youth.

Story of the Partnership

Most researchers come to partnerships with beliefs, usually research-informed, about what good learning looks like in a certain domain; and often have an associated design conjecture in mind. In addition, researchers often have pre-existing commitments to a particular strategy, tool, system, or approach to try to reach their goal, for example, to make learning happen more reliably, for more people, more of the time. We had a strong hunch that documentation was vital to good learning in creative learning settings. So in seeking to develop good partnerships, we needed to be clear about those beliefs and commitments; then be truly open to changing them as we negotiated, shaped, and gave shared language to the form that the research and design inquiry would take with our practice partners. Our negotiation process unfolded through a series of carefully crafted generative design workshops and lo-fi prototyping engagements. We also kept a dialogue open with our partners to ensure mutual benefit outcomes were centered as the relationship and project evolved.

To open up the research space, we drew on a co-design process and participatory methods to engage educators, stakeholders, and the research team in imagining and defining together what documentation is, why it matters for creative learning, and how we might encourage youth to come to value it as a creative practice, not just as a required assignment or formative assessment. Only then did we begin collectively exploring possible ways to support documentation practices through a series of generative and syncretic practices: (a) workshop engagements, which begin with space tours and inventories; (b) framing activities to identify pain points and values; (c) generative workshops to ideate concepts; and finally (d) collectively choosing concepts for prototyping based on promise and feasibility.

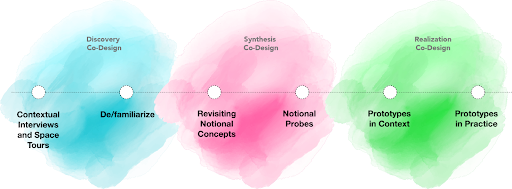

Core to our engagement approach is a carefully orchestrated set of co-design activities that sought to solicit concepts and possible design enactments in a process summarized in Figure 2. Conducted in a workshop format, the activities were iterated and refined with stakeholders across three contexts. Participants included instructors, program coordinators, staff, and in some cases administrators. We began with the aim to build a shared understanding of documentation (both as a noun and verb), discussing how it benefits their curricular programming and capturing the type of challenges encountered when facilitating documentation practices in the educational setting. The workshops then transitioned to exploring relatively familiar, low-cost technologies and imagining together ways that these could be used to scaffold documentation practices. The remainder of the workshop was dedicated to a series of guided ideation activities that encourage educators to speculate on the ways in which various inputs and outputs (e.g., cameras and timelapse/video capture, live-scribe pens, thermal printers, NFC tags, smart home products, etc.) could be deployed to augment existing or foster new documentation practices in their classroom spaces. At the end of the activity, groups reported on and prioritized concepts supporting learning in technology-enhanced makerspaces. These concepts were carried forward as notional design concepts to further probe and later prototypes (see Figure 3).

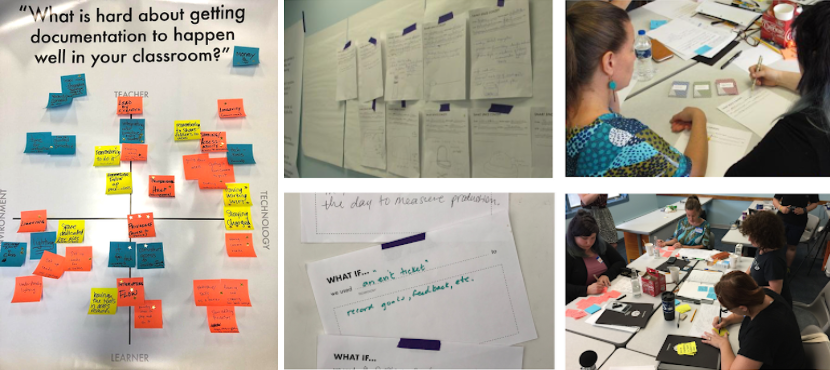

Figure 3. Participants in the co-design workshop initially identified shared values and challenges (left). This grounded a generative card activity designed to help imagine IoT-enabled solutions that support documentation practices and address challenges in maker and project-based learning contexts.

The focus on relatively familiar, under-utilized technologies in education also benefited our co-design approach. Within this work, we consciously chose to avoid more complex, futuristic technology possibilities to bring educators into the cooperative design of more tractable, near-term technology solutions that respond to pragmatic, immediate problems of practice that educational teams faced in their learning spaces.

In deployment, the creative adaptations of ‘tried-and-true technologies,’ like thermal printers and NFC tags, allowed us to rapidly prototype and realize notional solutions for early consideration. The focus on low-cost, robust solutions allowed us to be agile and respond quickly to shifts, uncertainties, and sudden changes in instruction. During the pandemic, we could quickly produce interventions that avoided complex assembly and uncertain technical infrastructures. These solutions had built-in consideration for students learning in widely diverse settings with varying access to technologies, toolkits, and support.

A related benefit was that our students, who were funded through an NSF Research Experience for Undergraduates grant, were able to team together to develop these relatively simple prototypes over the course of a semester or summer project and gain experience in a full research-based learning innovation cycle.

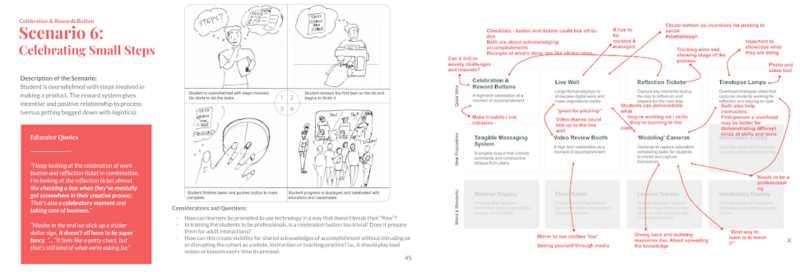

Practice partners were re-engaged through synthesis workshops to share back insights, clarify design directions (see Figure 4) and decide the next steps. For example, at the high school site, participants prioritized three concepts relating to ways in which augmented tools and materials themselves could help students learn how to use them effectively by documenting past interactions with (other) learners. A concept from one participant imagined a smart parts bin where “[a]s a user comes to materials, [the device] tracks materials they look at and take/put back. Students then “get a list of considered/used/returned materials” to help them identify relevant online tutorials and guides, and to support the creative exploration of parts as they apply to assigned project work. Educators voiced a second, and similar, concept: the design of a parts bin that would help students to “understand the purpose of complex parts and their effectiveness” by allowing a student to select materials or parts which would trigger “text and describe the use of parts and materials through video and images.” This concept also included the idea that students could add to these descriptions based on how they had used the tool, giving richer resources to the next student to use the same material or part. These concepts were grouped as “tools with histories” and were prioritized by educators as one for further iteration.

Figure 4. Synthesis workshops presented initial concepts and scenarios based on the generative workshop (left). Instructional teams were invited to share responses, clarify needs, and refine implementations by marking up the concepts (right).

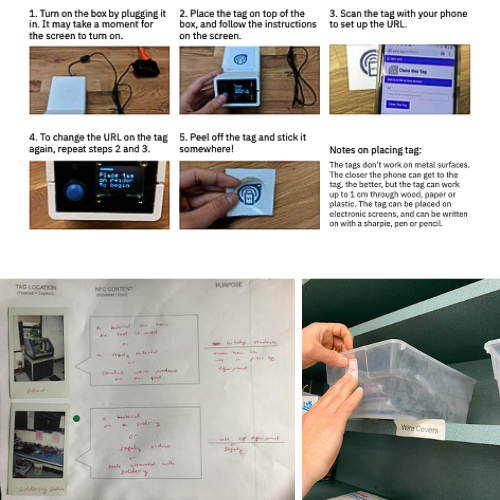

Moving to the next phase of co-design, we rapidly prototyped initial versions of the potential tools envisioned for the instructional teams to encounter. Prototype review sessions allowed educators to experience and respond to material embodiments of the design concepts selected (see Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 5. At Startable, we presented a series of early functional prototypes to a group of educators and students within the program.

Figure 6. Prototype example for the ‘Tools with Histories” concept with an NFC tagging system to allow objects within a makerspace to be quickly annotated with digital information. Each tag can be configured to redirect to a web resource (e.g. an instructable or guide) or to a wiki page that can be collaboratively edited by the learning community. Top: Step-by-step set up of an NFC tag. Bottom: A synthesis workshop where educators brainstormed opportunities and deployed tags in the makerspace

Lessons Learned

Our goal was to translate selected concepts into situated encounters with prototypes in the learning spaces. It was, however, disrupted by the pandemic. Working closely with our practice partners, we rapidly shifted the design focus from adapting documentation-related priorities to something that could be deployed in remote and hybrid learning contexts. Collaborating online throughout the summer and fall of 2020 with our practice partners had some surprising upsides; online meetings were normalized and increased the ease and frequency with which we could gather for decision-making, iterations, and tracking how the learning interventions were being adapted in the pivot to remote instruction. The products piloted included the Self-Directed Learning Kit and ioRef: Electronic Parts Cards, illustrated in Figures 7 and 8, which were deployed to students throughout 2020 and 2021.

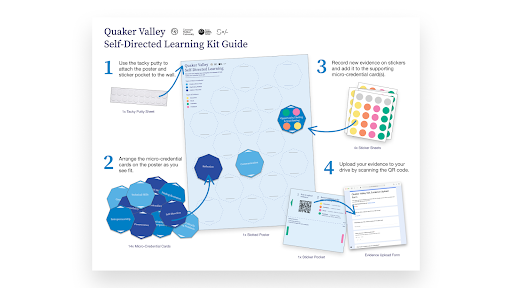

Figure 7. Above: The Self-Directed Learning (SDL) kit is a documentation toolkit for high school students that spans home-to-school settings. The SDL documentation poster kit integrates a visual progress tracker linked to a digital system for uploading, tagging, explaining, and curating evidence. Findings on student use and teacher insights from our Spring 2021 deployments to more than 60 students found it enhanced articulation and reflection on evidence of learning.

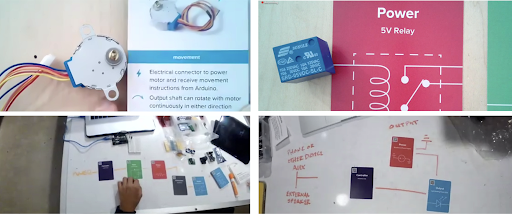

Figure 8. Above: IoRef is an instructional and creativity support tool for introductory physical computing courses. It adapts the ‘tools with history concept’ and builds on a QR-code-enabled card deck illustrating electronic parts and categories linked to an online knowledge base to help bridge access to creative know-how. Below: Through deployment in five courses, we found the IoRef documentation system to be a versatile resource for learning to recognize electronic components, enhanced communication in early designs and in debugging, and aid in schematic diagramming.

We’ve just provided an overview of an intensive, involved, cooperative design process that was deeply engaged with a series of practice partners over multiple years, sites, and program instances. This work reemphasized for us the importance of creating timelines that recognize the funding and labor needed to undertake slow, deliberate work open to shifts in priorities and pragmatics. Our partners appreciated sharing of well-designed communication materials and opportunities to showcase the joint work in their professional circles, as well as opportunities to contribute to our publications and presentations.

The project was also a reminder about how important it is to identify valued practices, and in this case, layering onto the existing cultures of documentation at each site, rather than trying to inject new approaches or tool adoption routines. We see co-design as a vital learning design research approach that needs to be better understood and practiced. Co-design offered us a means not only to arrive at highly valued learning interventions but ones that recognize, support, and amplify practices at each site. Co-design also offered us a means to intentionally shift the design focus and consider more fully how technologies can support key learning practices through documentation activities.

Next Steps

This experience has led us to reflect on our co-design practice. One insight is that we need to develop workshop arcs with partners that more fully include and recognize the ways that diverse practitioners and professionals want to participate in research-based learning innovation projects. The work has served as a reminder to us that if co-design is promoted as a more ethical, equity-centered, and justice-oriented way to engage in educational research innovations, then we need to pay much closer attention to the subtle and nuanced ways in which co-design is conducted. The prompts and forms of playful activity, the materials and skills used to creatively ideate, and the facilitation styles and timing of workshops, to name just a few considerations, can unintentionally exclude people from full creative participation in the design work. When successful, co-design methods create spaces and repeated opportunities for all participants to feel heard, energized by the possibility of mitigating persistence problems of practice, and to be fully seen as creative agents and innovators able to shape alternative educational futures.