Seeing the World through a Mathematical Lens: A Place-Based Game for Creating Math Walks

by Koshi Dhingra, Candace Walkington, Elizabeth Stringer, Marc T. Sager, Saki Milton, and Anthony J. Petrosino

Key ideas

Working at multiple sites helped emerging scholars see how to identify strengths of partners and draw on their contextual knowledge to shape program designs. Exposure to diverse research sites allowed emerging scholars and senior researchers to identify issues and fill in gaps across the contexts. In trying to build on K-12 students’ funds of knowledge, emerging scholars learned how challenging it is to design interest-based math problems that are relevant to them and convince staff to let students take ownership of the activities.

Background

The goals of Seeing the World through a Mathematical Lens: A Place-Based Game for Creating Math Walks (NSF grant DRL 2115393; also known as “MathFinder”) are: (1) the development of a mobile app that allows youth to create and use “math walks” at informal learning sites, (2) research on how math walks can be best designed to enhance student outcomes, and (3) the development of a network of community-based organizations engaged in informal mathematics education. This project is a partnership among Southern Methodist University (both the Simmons School of Education and Human Development and Guildhall program for video game design); talkSTEM, a community-based nonprofit organization; WestEd, an education research nonprofit; and nine informal learning partner sites in Dallas. These partners include the Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas Arboretum, Dallas Zoo, Frontiers of Flight Museum, Girl Scouts of Northeast Texas, Voice of Hope Community Center, Twelve Hills Nature Center, St. Philip’s School & Community Center, and the Girls in Engineering, Mathematics and Science (GEMS) camp. The partner sites are widely varied with regard to their structures and sizes, the complexity of their administration, the number of youth served annually, and their physical locations.

The MathFinder partnerships are grounded in a five-year NSF Advancing Informal STEM Learning grant, which launched MathFinder, a community math walks initiative. Mutual trust and understanding developed between SMU and talkSTEM as they collaborated. Collaborations between the School of Education at SMU and the Guildhall at SMU were also established over this period, as the two groups began working on educational game projects together. The relationships with the nine informal learning partner sites were developed between talkSTEM and most of these organizations both previous to the start of the project as well as over the period of time that the MathFinder initiative was launched. Many of these partner sites were interested in implementing math walks at their sites or training their personnel in math walks even prior to the start of this project. The MathFinder project enabled us to build on these long-term collaborative relationships.

To explore the details of how this project prepares early career researchers, we continue with two perspectives, the PI’s perspective and the graduate students’ perspective.

Perspective One: How the PIs Designed the Project to Support Student Growth

by Koshi Dhingra, Candace Walkington, and Elizabeth Stringer

As described throughout this report, partnerships are valuable because they increase the richness of the technology being developed, the quality and applicability of the research being conducted, as well as the perceived relevance and value for those with whom the technology is being developed. Since partnerships necessarily involve collaboration across institutional cultures, it is important to build an understanding of and respect for the varied habits, activities, and priorities (i.e., the cultures) that are integral to the identity of each partner organization. A deep understanding of the different organizational structures and cultures is critical because, in the absence of this, wonderful technologies with huge potential go unused. To scale usage, researchers and developers must have a nuanced understanding of the practices of the partner organizations that represent the user population. We sought to involve our early career researchers in developing this understanding.

Children interacting with the app in the current state of development at a recent MathFinder research camp at the Voice of Hope Ministries.

Preparing Researchers to Interrogate What Count as Mathematics

One way that this project prepared researchers to be good partners was encouraging them to ask “what is math?” Math is often defined in one of four ways: (a) academically, or (b) from researcher perspectives, or (c) from math teacher perspectives, or (d) based on policies and standards. In this project, the informal learning sites determine what mathematics is, where it is, and what it can be – based on their experience with visitors and learners. By considering partner perspectives, researchers learn to question their own preconceptions about mathematics and to elevate real-world, place-based activities.

Preparing Researchers to Conduct Research on Partner Contexts to Inform Design

The graduate students who are on this project team are trained to gather insights into the priorities, practices, and perspectives of multiple informal learning sites and their personnel, all of whom operate under vastly different constraints and realities. The graduate students learn to recalibrate their expectations as they move between varied partner sites with different resources and styles. For example, at an after-school club in an under-resourced neighborhood of Dallas, learners in the club already have strong relationships with instructors. Our graduate students observed strikingly different interactions between participants and instructors in a three-day long camp at the Dallas Zoo, where the instructors and youth did not know one another. As emerging scholars work with these different partners they gain experience in learning to listen and adapt to the different and unique values, norms, resources, and needs at each partner site.

Building this kind of understanding increases the likelihood that the technology we develop will successfully engage the groups we aim to serve. As we began designing the app, there was necessarily ongoing dialogue about the needs of each site, the ways in which the programming and the app needed to change to improve usage and outcomes, and constant recognition of and discussion about constraints. These ranged from lack of WiFi capability at some sites, to multi-floor buildings at other sites where GPS coordinates were ineffective in pinpointing specific math walk stops. This also related to the differing structures for the math walk activities used at each site. The activities ranged in the amount of time allocated, the mathematical content, and the existing walk stops. As an example, at the zoo, where a key educational goal is to be screen-free during educational programming, youth observe animals in their habitats. Here, emerging scholars worked with the zoo personnel to imagine a solution where youth would comfortably use the app in a way that does not conflict with their key goal. To do this, we came up with a structure where most of the app usage would be in a separate zoo classroom, at a time when students were not interacting with the animal exhibits.

Children interacting with the app in the current state of development at a recent MathFinder research camp held at Twelve Hills Nature Center in Dallas.

Preparing Researchers to Co-Design With Youth and Informal Educators

This project also prepared researchers to engage in community-based co-design work, rather than design a study and then seek a site for implementation of the study. The co-design process with community sites involved observing youth at their sites going on and creating math walks without technology, led by site informal educators. It also involved focus groups with youth and informal educators at the sites. In co-design, our partners from the informal organizations are seen as researchers too. Design decisions are made in partnership with key stakeholders – including the kids that will use the app and the informal learning sites that will support the app. This positions researchers not as the “authority” who are passing on their innovations to educators and kids, but rather as facilitators who help to support the potential of their partners and allow their unique strengths and resources to truly shine.

Observation and feedback about youth participation at each research site were rich and from multiple perspectives.The team engaged in listening to the feedback and was open to revising major portions of the project. For example, an observation from the informal educators that the youth needed more support posing their questions for their own math walk stops led to the development of additional video resources and app mechanics – even though the original plan had been to make this activity a more traditional, less-guided inquiry.

Lessons Learned

Involving early career scholars in this project has helped them develop an appreciation for the amazing co-design work that can occur among a diverse array of community partners and researchers, and learn how to develop technology-supported activities that helps meet their needs in working with youth, while also advancing fundamental knowledge of how people learn with technology. Our partnership work has further highlighted for the early career scholars the power of emerging technologies to adapt to the varied needs of many different stakeholders in education settings, operating under a variety of constraints and with different goals. Finally, this partnership work has highlighted the important insights that kids themselves can give when asked to help design technology systems.

Just as important, our project has also enabled our early career researchers to have a realistic understanding of the costs of this approach. Activities like reaching out to and meeting with partners individually, engaging in co-design processes, building site-specific capacity through individualized resources like math walk videos and training sessions, and providing encouragement and support to sites as needed, are very time-consuming. In addition, it is important to recognize that in long-term projects such as this, strong and sustained top-down relationships with organizations are also needed, given the complexities of organizational structures, shifting priorities, and changing staff.

Perspective Two: What Early Career Researchers Gained From Their Experience Doing Partnership Research

by Marc T. Sager, Saki Milton, and Anthony J. Petrosino

The first and second authors of this section are doctoral students at SMU working on the MathFinder project. We have received invaluable research experiences, such as the development of complex community-based research designs and experience with implementation, data collection, data analysis, and dissemination of research.

During the first year, we were able to participate alongside the Principal Investigators in the implementation of the research project at three partner sites. As such, we observed “behind the scenes” activities associated with preparing a complex and large-scale research project. The MathFinder project included working with a large and diverse set of individual stakeholders to ensure that we researchers are prepared to use equitable lenses in our research and development. Each researcher also brought their own valuable prior and lived experiences and knowledge to strengthen this project, whether that be work experience, teaching and pedagogical experience, or methodological and data analysis experience.

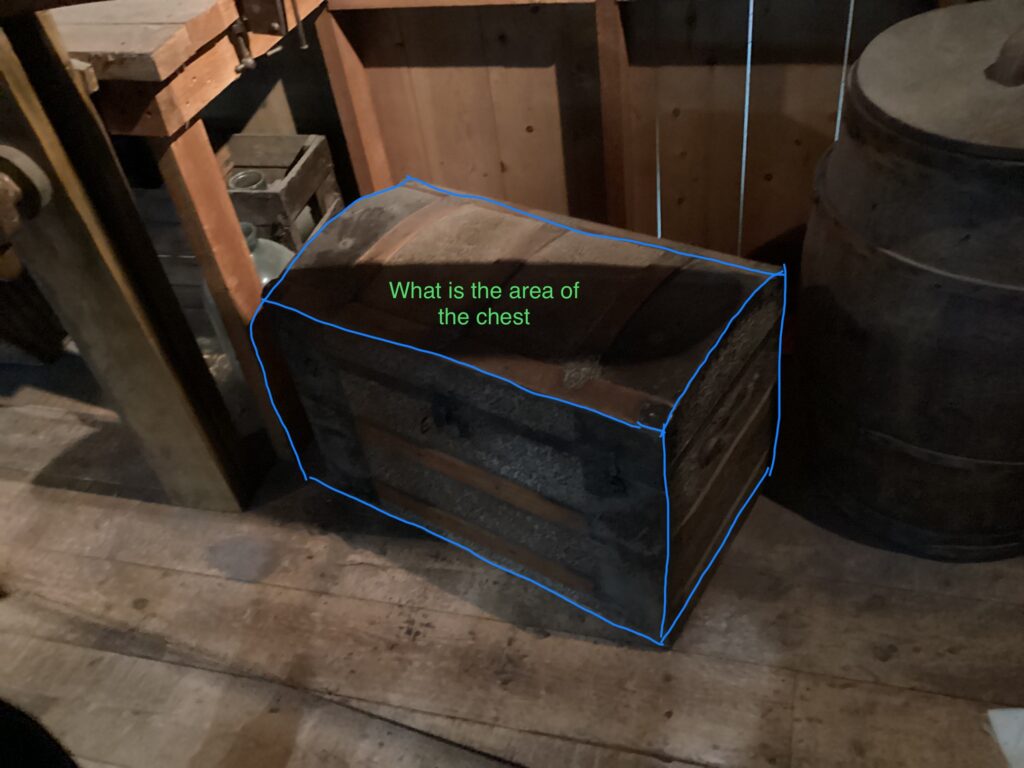

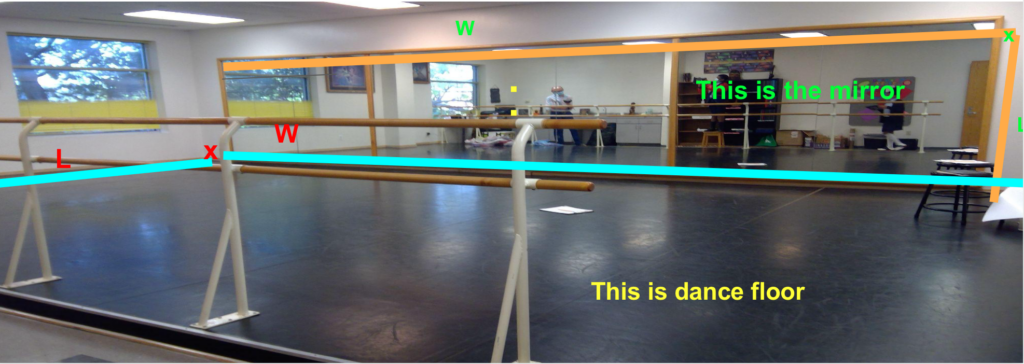

“Community Center”: St. Philip’s School and Community School Example – What strategy(ies) can you use to compare the area of a dance floor to the dance room mirror?

Learning to Do Partnership Research

Preparing early career researchers requires introducing them to fundamental conceptual and theoretical knowledge and supporting literature, which guides the research. This project drew upon informal math learning and the theoretical concepts that we learned about came from interest theory, problem-posing, and culturally sustaining pedagogies. We were trained to use these concepts to design cycles of participatory design-based research on technology-supported math walks. We hypothesized that math walks may trigger and maintain students’ interest in learning mathematics (Hidi & Renninger, 2006), increase math ability beliefs (Perez-Felkner et al., 2017), and lower math anxiety (Bai et al., 2009). The data we collected and analyses we ran helped us connect the literature to real-work experiences regarding these constructs.

The project trained us to use research-practice partnership (RPP) tools and routines from Penuel and Gallagher (2017) to support the partnership’s infrastructure, such as: (a) working through the logistics of scheduling meetings and professional development events, (b) using multiple communication modalities (i.e., emails, Zoom meetings, in-person meetings, Slack) to ensure all parties involved were engaged in conversations, (c) setting agendas to facilitate discussions, (d) using both Google Drive and Box to support collaborative efforts and house documents, and (e) establishing formal agreements, including research compliance from the university’s Institutional Review Board (IRB).

With this RPP approach to research, we established a process that respected students’ funds of knowledge, especially those of students from underserved communities and schools. Doing so helped us implement our project in ways that support learners, to ensure asset-based strategies for accessing the mathematical content and practices being explored at the partner sites. We saw how math walks, facilitated through game-based digital technology that position learners as problem designers, could potentially spark learners’ interest in and curiosity for mathematics. These math walks could also act as a vehicle for integration across STEM. This helps students collect and analyze data with a greater sense of alignment with the purpose statement and research questions being investigated. Having the opportunity to engage with ideas at both the conceptual and practical level helped make the theory clearer and more relevant to us.

We both acted as adult facilitators and engaged in video recording for data collection purposes while at these sites. We were able to identify: (1) How the adult facilitators unintentionally influenced students’ mathematical learning and problem-posing by replicating school mathematics (Sager et al., in review), and (2) the importance of fully capturing students’ embodied actions with the video recordings. Additionally, we have been extensively supported by experienced researchers with our data analysis using methods like interaction analysis (Jordan & Henderson, 1995), conversation analysis (Goodwin, 2007), and thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The greatest takeaway for us was that the conventional way that middle school students learn mathematics in formal schooling adversely impacted their attitudes toward math, anxiety toward math, and efficacy while doing mathematics (Milton et al., in review).

Another skill we gained from working on this project was how to disseminate our work. Both of us authored conference proposals for the annual American Educational Research Association (AERA) conference and the International Conference of the Learning Sciences (ICLS). Currently, we are both preparing manuscripts for high-impact journals using data from the project: Marc’s journal article looks at the adult-student power dynamics that influence learning, while Saki’s journal article looks at students’ attitudes toward math and challenges associated with student group dynamics in mathematics learning during the math walk activities. These articles are not the typical kinds of papers that report on project findings, but ones that reflect on how to structure effective partnerships with youth.

Lessons Learned

As early career researchers, we have learned that being a good partner entails full participation and open communication. The quarterly partner meetings are excellent examples of what this looks like in action. At those meetings stakeholders shared updates from their experiences with the research team, ranging from collaborative data analysis to the latest developments of the MathFinder app prototype. They offered constructive feedback to strengthen the partnership (Wang et al., 2021). In addition, we also had to communicate our findings back to the site to ensure that we were achieving the goals of equitable place-based mathematics. Prior to the MathFinder’s program at each partner site, museum staff members received a professional development workshop that centered around the three math themes of the grant, facilitation strategies, and methods for scaffolding to support the fidelity of implementation. However, during our data collection and analysis, we noticed the facilitators influenced students to think canonically and traditionally about mathematics, problematizing place-based ideas. Moving forward, we will work with facilitators to use a more “hands off” approach by focusing on video recording group interactions and discussions, as well as emphasizing students’ funds of knowledge to ensure student problem-posing is authentic and of interest to the participants.

Through this experience we have also learned more about how to create and contribute to a collaborative multidisciplinary team. For example, because partner site representatives participate heavily in the data collection phase, in Year 1 they did not participate as much in the data analysis, the app development, or dissemination process. In our next phase of work, we plan to provide more support for partner representatives to participate in these aspects of the project. Our experience collecting and analyzing video data in Year 1 also taught us lessons about how to improve our research and collaboration. After facing challenges with the quality of the video in Year 1, we plan to analyze the video data after each partner site visit and before the next visit to improve our data collection, as suggested by the literature (Anderson & Shattuck, 2012; Brown, 1992; Design-Based Research Collective, 2003; Hoadley & Campos, 2022) and to demonstrate the iterative nature of design-based implementation research.

Finally, our experience engaging in co-design helped us learn that students bring their own cultural and familial capital, communication styles, and prior math knowledge to the learning experience. These characteristics need to be recognized and honored throughout the research process because they can inform innovative learning through the use of emergent technologies like AR and VR.