Executive Summary

As researchers seek to build knowledge in their fields and have a meaningful impact on society, the structure of research is rapidly shifting from individual investigators exploring their own questions to collaborations among investigators and partnerships with practitioners. Together, they decide what questions to ask, what data are meaningful, and how to interpret findings. For the last decade, the National Science Foundation (NSF) has strongly emphasized the need for collaboration and has specifically encouraged partnership in research focused on STEM education. Partnerships were at the core of NSF’s Math Science Partnerships initiatives and two of its “10 Big Ideas” for future investment – Convergence Research, with its focus on integration across disciplines, and NSF INCLUDES, which catalyzes collaborative work for inclusive change. The EDU Directorate of NSF continues to prioritize partnership as it considers how to advance research to address the issue of the “missing millions” in STEM identified by the National Science Board.

We observe, however, that “partnership” can mean many things – from two universities working on separate pieces of a large project, to a Research Practice Partnership between a school district and an education institute, to an interdisciplinary team of learning scientists and computer scientists, to game designers, students, and researchers co-developing a STEM game. For this report, we are interested in looking at a variety of partnership types, but through the lens of partner contributions leading to transformation, which may be transformation of a design, research questions, or even the research process itself.

This report is grounded in a set of case studies related to Research on Emerging Technologies for Teaching and Learning (RETTL) and similar projects. We chose this focus because the Center for Integrative Research in Computing and Learning Sciences (CIRCLS) hub serves a portfolio of NSF awards focused on RETTL. The theme of how to create effective and lasting partnerships arose as a priority in our last community convening in 2021.

Further, the awards in the RETTL portfolio feature exploratory research – and exploratory research should foster transformation. In fact, the awards require partnerships among computer scientists and learning scientists, and transformative partnership is an intrinsic part of the program. The solicitation states: “Emerging technologies have the potential to transform teaching and learning, in both formal and informal settings, particularly in support of STEM learning outcomes.” Shortly thereafter, it states: “Given the complexities surrounding the development of technology and learning environments, high-impact research requires interdisciplinary teams.” Going beyond teams only of researchers, the community heavily emphasizes an applied orientation to education in its research and the need to partner with practitioners and other participants through the research process. In short, the CIRCLS community is fertile ground to examine the nature of transformative research partnerships.

What kinds of transformations are possible?

Across an initial set of four case studies, we uncover how strong partnerships result in transformation of the research vision and initial design commitments, and how they can even lead to considerable reframing of the core research questions at the heart of an investigation. All of these case studies share a commitment to “co-design” – a process in which researchers share power with practitioners to design an exploratory use of technology for learning. Co-design is distinct from light-touch engagement with practitioners that commonly occurs through focus groups or field tests. Through the co-design process, the practitioner’s perspective and voice deeply influences the design itself. Below are summaries of these cases.

- Co-Designing an Introductory Coding Platform: To engage more students in learning computer science, a partnership among researchers, local teachers, and a local chapter of the CSTA developed a new vision for a coding platform: a platform grounded in students’ creativity, design thinking, and their desires for freedom. The team found ways to refocus away from syntax and toward a problem-centric curriculum, and they learned that incorporating visualizations and non-technology activities was essential to student learning.

- Co-Designing Maker Spaces: As partners sought to create an effective support system for students’ self-directed learning in maker spaces, new visions for “documentation” tools emerged with a shift toward design solutions that shortened the distance between physical and digital resources. The case reveals how strong commitments and execution of a well-specified co-design process enabled dramatic changes in the research project, changes that better suited students’ needs and learning environments.

- Co-Designing Augmented Reality: As partners explored augmented reality experiences for community college astronomy students, initial presumptions about student roles and the goals of the classroom activity quickly fell away. The design concept and research investigation shifted to focus on giving students “shared representational spaces” to productively exchange knowledge and make meaningful references to important artifacts and variables across technologies.

- Co-Designing a STEM Learning Game: As game designers collaborated with neurodivergent college students to co-create an educational game about space exploration, the possibilities for what the Principal Investigator (PI) imagined might be up for negotiation expanded substantially. The project team took the time to integrate appropriate accommodations into the work process, enabling full and meaningful participation of all participants, whose voices were heard and whose ideas led to significant changes in the game characters, narrative, and interface.

In these cases, we see that partners transform the core vision of an exploratory research project with emerging technologies, often causing researchers to abandon presumptions about their design and their research questions. As they honor practitioner voices, the researchers re-focus on designs and research questions that are more relevant to practice. Resulting exploratory designs are a much better fit to educational environments and partners’ learning goals. In summary, co-design involves sharing power with practitioners so they can play strong roles in reshaping the project vision, its design premises, and the research questions to align with educational priorities.

How are partnerships structured to be transformative?

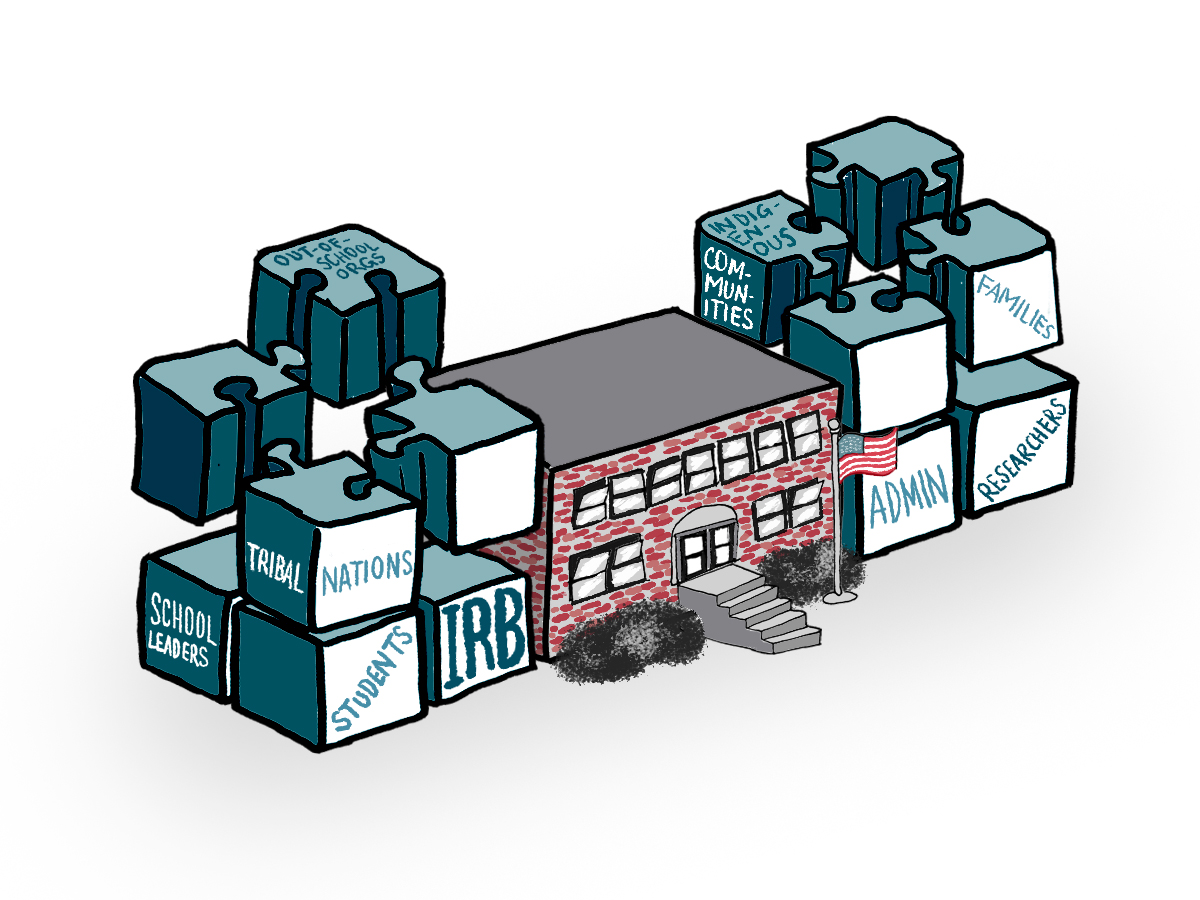

Partnerships can challenge core structural elements of research projects, for example:

- Institutional Review Boards (IRBs): In an exploratory project in which Indigenous communities used technologies to enable families to share knowledge about their connections to the land, the project team partnered with the IRB to define how ethics and social justice could be honored and strengthened through research.

- Advisory Groups: As CIRCLS brought together practitioners to create a framework for school adoption of emerging technologies (such as Artificial Intelligence (AI), Virtual Reality (VR)/Augmented Reality (AR), and use of an expanded set of sensing and visualization technologies), the team re-thought the process for creating and structuring an advisory group in a research project – transitioning away from providing feedback to researchers and toward empowering practitioner voices.

- Interdisciplinary Meetings: An AI Institute encountered challenges in finding common ground among its computer scientists (CS) and learning scientists (LS), and restructured the dialogue between these disciplines. They found that a conjecture map tool helped CS and LS researchers see how their different values and perspectives fit together, and helped them develop “conjectures” about their research that would be meaningful to both groups. Further, the adapted conjecture map helped the interdisciplinary teams consider risks of AI in their exploratory research.

In these cases, we see that in partnerships for change, the partners examine typical infrastructural components of research – the IRB, advisory groups, and interdisciplinary meetings – and then dramatically reframe these roles to enable the infrastructure to more directly and strongly achieve the partners’ research and development goals.

How can we build capacity for partnership?

Demonstrating a commitment to partnerships will require that our community builds its capacity to prepare early career scholars and institutions that do not often receive research funding to engage in this kind of challenging and valuable work. Establishing a set best practices for creating replicable partnership procedures will involve learning what effective programs are already doing. In the final section, we present two cases that illustrate how to build capacity for partnership.

- Among early career researchers: In the first piece, we learn about a project that co-creates technology enhanced math activities with and for a variety of informal STEM organizations. The lead researchers on this project describe how they structured research opportunities to prepare early career researchers to be good partners with community-based organizations and engage in high-quality partnership research. We also hear from the graduate students who were trained in this project, including what they learned about partnership research from their experience engaging with community organizations and youth.

- At Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs): In the second piece, we learn about an HBCU with close ties to its local community that brought together high-tech industry, research, and workforce development partners to co-create a robotics and data science program to inspire high school students to see pathways into the STEM workforce.

These pieces provide concrete examples of how working with partners, especially community-based partners, is essential for building future capacity for rigorous and meaningful research on emerging learning technologies.

Recommendations and Next Steps

In reviewing all of the cases of partnership presented in this report, the editorial team generated six recommendations for structuring, sustaining, and building capacity for transformative partnerships in our work:

- Establish partnerships before developing projects. Researchers should establish partnerships early in project development because these relationships will change their vision for the work.

- Allocate time and attention to establishing equitable procedures for doing partnership research. Authentic involvement of a diverse set of partners strengthens our projects, but researchers have to be mindful that structuring equitable and supportive partnerships takes time and effort.

- Co-design the ideas for research, development and programs with partners. Our partners need to be the drivers, not the recipients, of our work and should play a key role in all aspects of the project, including research design and outcomes.

- Establish the emerging technology as a place for dialog and synergy, where all partners have something valuable to contribute. It is essential for teams to create open and accessible technologies so that teachers and students can contribute as much to the design of new learning technologies as programmers or graphic designers.

- See changing the research designs, questions, and processes based on partner input as a feature, not a bug. We engage with partners, especially practitioner and youth partners, not to get their approbation on our designs, but their honest opinions based on the experiences they have using them in real-world situations.

- Build capacity for valuing partnership research. Partnership research is not what many research communities or academic disciplines understand as “research,” but it is essential for creating effective designs for technology-enhanced learning.

The CIRCLS team and its community look forward to continuing our progress toward understanding transformative partnerships in our upcoming convening and in our community’s future work. The approaches outlined in this report can lead to innovative exploratory research with emerging technologies and concrete strategies to bring the “missing millions” into STEM by partnering with stakeholders, often in historically marginalized communities. We hope these examples will encourage dialogue with other NSF initiatives as well as others who are exploring how research partnerships can be transformative.

Explore the Partnership Themes

Back to top

Download the CIRCLS 2023 Community Report (PDF)

Download the CIRCLS 2023 Community Report (PDF)